Rethinking Hydro-Diplomacy: The Bridge Tank holds a high-level panel on the side of the UN-Water Summit on Groundwater 2022

On December 6th, 2022, The Bridge Tank held a high level panel discussion on hydro-diplomacy in Paris, on the side of the UN-Water Summit on Groundwater 2022, coordinated by UNESCO.

This event was placed under the high patronage of:

Mrs. Irina Bokova

Co-chair of the International Science Council’s Global Commission on Science Missions for Sustainability and Former Director General of UNESCO

Mr. Erik Orsenna

Chairman of the Initiative for the Future of Great Rivers (IAGF) and Academician at Académie Française

Context

The conference focussed on “Rethinking Hydro-diplomacy: International Rivers as Instruments for Peace. Shared experiences, solutions, and sustainable resources management” and was organised and consciously positioned in the context of the United Nations’ renewed focus on water. The 2023 UN Water Conference planned in New York, in March, will be the first event of this kind since 1977.

As issues of water wars and conflicts rise in prominence due to increased hydric stress around the globe, hydro-diplomacy is bound to be a crucial subject in the years and decades to come. Following the recent release of our policy brief, which called for a renewed and enlarged practice of hydro-diplomacy, this conference represented the logical continuation of The Bridge Tank’s wish to position itself and contribute to the field and practice of hydro-diplomacy.

Objectives of the conference

Convinced that hydro-diplomacy is not only the practice of diplomats and state entities, the conference aimed to offer a reflexion and exchange on the development of tools for hydro-diplomacy and towards the de-escalation of water-related conflicts.

The Bridge Tank thus convened this panel to gather like-minded people dedicated to a better approach and management of water resources. These included esteemed policy and decision makers, aid and humanitarian organizations, researchers, legal experts, and practitioners involved in water-related issues.

The event was held in hybrid format, allowing for a participants from across the globe to share their experiences, success stories, case studies, and the challenges they encountered. Participants joined from Abidjan, Brussels, Conakry, Dhaka, Geneva, Marrakesh, Oslo, Paris, Skopje, Tashkent, and Tokyo.

Valuable discussions on water and hydro-diplomacy

The conference started with an introductory session setting the stage for the day by providing an overview of the existing international system in place on questions of water and introducing existing hydro-diplomacy initiatives and experiences from non-conflictual and integrated development water co-management. These introductory remarks stressed the need to approach water from a wider point of view, as a societal issue requiring shared and multi-stakeholder solutions and approaches. Co-operation is particularly needed in response to environmental and ecological threats on the one hand and to contribute to global peace by reducing the risks of violent escalation and water conflicts on the other.

The first thematic session of the day gave the floor to political decision makers from around the globe for them to share and discuss their experience with water and its management. Key messages included a call for solidarity of actions between all stakeholders in the face of crises and the need to listen to and believe local communities. Participants here again underlined the need to address water issues in a holistic way, an idea which requires an integrated approach to water management. Other key points raised included the need to combine both local management with a larger scientific worldview and understanding.

The second thematic session turned to international aid and development actors. From their field knowledge and experience in development, participants mentioned the inter-connectedness of issues, as water is a factor and entry point to food security, health and early childhood development, energy development, disaster risk management, climate change, and questions of transport. The need for an integrated and multi-lateral approach to water on the one hand and the importance of local and community action on the other also found resonance during this session. Transboundary governance however necessarily requires political will to move forward. A final but crucial point addressed by multiple contributors was the role education and knowledge of the water resource in order to ensure better maintenance and management of river basins.

Finally, the last thematic session took on the task of discussing the diversity of tools at the service of hydro-diplomacy. Participants here again encouraged a community based approach, starting at the local level, to develop solutions tailored to the communities’ needs. The examples of River Basin Organisation must thus be understood in their variety, as their diverse forms are the result of the diversity of needs and functions they fulfil. The centrality of knowledge, data, and scientific research as necessary prerequisites for action were addressed by participants of this session as well. In addition to that, the ideas of shared infrastructure and shared water information systems were noted as promising tools for hydro-diplomacy.

Key takeaways of the conference

From the valuable contributions of the conference’s many participants and the lively discussions throughout the day, a diversity of approaches to hydro-diplomacy transpired, allowing for the establishment of what could be defined as a taxonomy of hydro-diplomacy.

We identified 3 key lessons learned:

1. A first aspect of hydro-diplomacy is found in its fundamentally diplomatic dimension, through its role in conflict prevention and de-escalation. Participants agreed to recall the classical approach of international law, which remains very much rooted in water issues.

2. From this early assessment, numerous contributions stressed the centrality of political will in hydro-diplomacy. Testimonies and experiences from across the globe provided ample proof that hydro-diplomacy initiatives like River Basin Organisations (RBOs) can be successful vectors of peace, cooperation, and sustainable management of water resources. However, all these initiatives and transboundary organisations presuppose and require political will.

- Discussions on how to generate this necessary political strongly focussed on a bottom-up approach, which in turn underlined the importance of local action and what could be called Track II hydro-diplomacy. Civil society’s knowledge and activity in the preservation of riverine and water resources combined with the exchanges between practitioners and scientists from different countries offer the foundational track II hydro-diplomacy needed to generate political will at the level of decision makers.

- From there, political will can be triggered through the interaction of the scientific and practitioner communities on the one hand and political decision makers on the other. As however pointed out by participants, bridging the gap between scientists and decision makers is not without challenges. Interactions between these two communities aimed at ensuring an increased commitment to hydro-diplomacy require aligning messages and preoccupations of both communities. There is therefore a real need for scientists to not only communicate the scientific importance and relevance of hydro-diplomacy and of an approach to water resources built on cooperation and co-management but also to stress its political importance. Hydric stress endangers entire communities in their livelihoods, creating insecurity, and accelerating both internal and international migration.

- Mobilising science and putting it at the service of policy making and the generation of political will has therefore been one of the key questions and preoccupations raised throughout the day.

3. A last dimension of this taxonomy of hydro-diplomacy which emerged throughout the conference was centred on the diversity of tools, processes, and institutions of shared management of water resources as well as discussions about their replicability.

- River Basin Organisations are notable examples of such institutions and developers of tools towards an improved management and sharing of transboundary water resources. With examples from the Senegal River, representatives from the Netherlands and France discussing the shared management of the Rhine River, perspectives from both Pakistan and India on the Indus River, as well as contributions from Uzbekistan with the example of Central Asia, the conference revealed the diversity of approaches and structures of RBOs and shared management agreements.

- Participants from the realm of development agencies addressed the question of replicability of RBOs by noting the comparative advantages of certain structures over others. They however also pointed out that each national and transboundary context, geography, and concrete local and regional needs require adapting the structure and form of RBOs.

- One final but crucial point raised was that cooperation fundamentally requires the sharing and pooling of knowledge and information. While it is important to respect national and regional sovereignty, global and transboundary issues like climate change and increased hydric stress call for global and multilateral solutions. Creating transboundary solidary and cooperation is necessarily achieved through the sharing of data.

A renewed and enlarged practice of hydro-diplomacy thus requires a durable platform of exchange between all stakeholders, bridging the gap between the scientific community, local water practitioners, and political decision makers. Honouring its name and mission statement, The Bridge Tank offers to provide this missing bridge and to host such a platform of exchange and connection.

This conference provided a first example of The Bridge Tank’s dedication to the matter and is hoped to become an annual occurence as the “World Water for Peace Conference.”

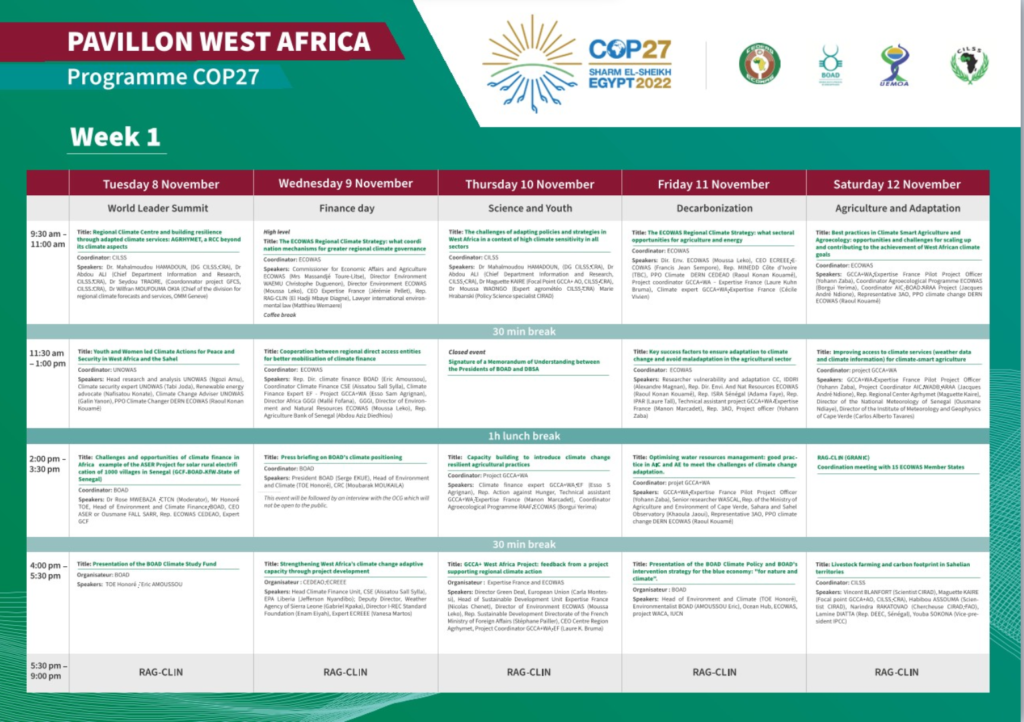

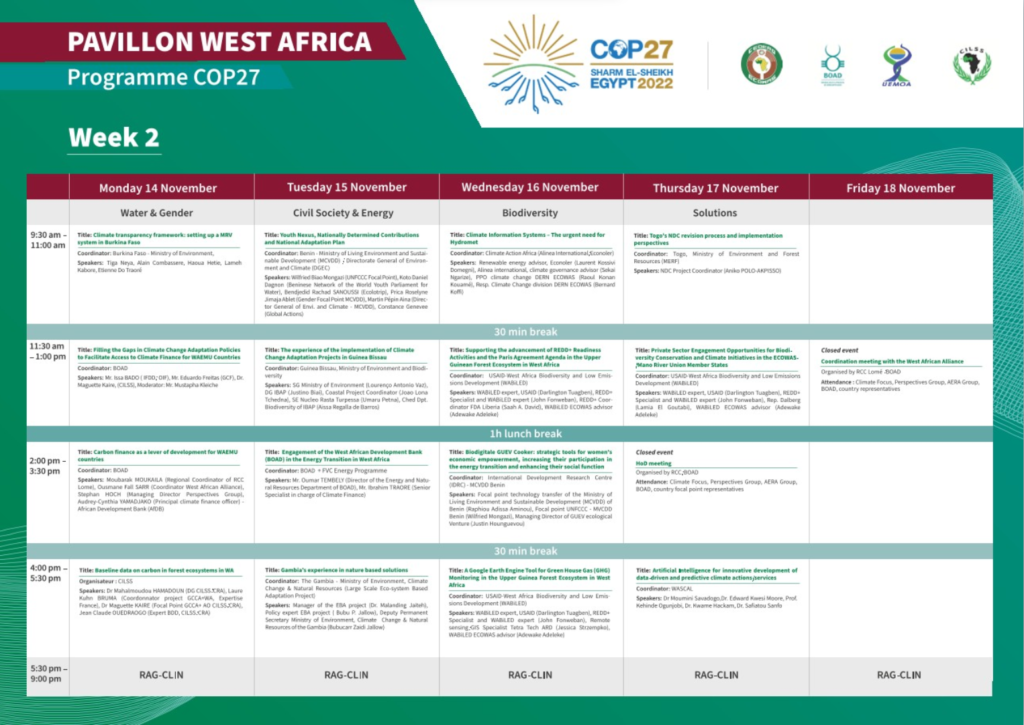

Read the concept note and the agenda of the day here.